Whiteboards and Warships

“Oh, interesting. I haven’t seen it solved this way before. Can you think of another way?”, the interviewer asks me, his face unemotive. His cursor highlights a line of code within our shared whiteboarding space — 20 lines of code standing in as a proxy for my technical ability. I obliged, but a refactor felt excessive. I wondered if the interviewer could sense my frustration through the impersonal lens of our video call.

That was just a moment from the technical half of the second interview in a four-part “loop” - the interview process which follows a near-universal template in software engineering. First a recruiter phone screen. If the hiring manager is interested, then a conversation to see if you’re worth the investment of a “full loop”. The loop varies, but an average loop has ~4 hour long interviews, featuring technical and non-technical portions. The thing that frustrated me about that particular loop? It was for an internal transfer- the same role, title, and responsibilities.

It wasn’t a difficult problem - but it already felt tedious before the requested refactor. Before the loop, at the hiring manager’s request, I delivered a document compiling my best designs, code commits, and artifacts, with links and descriptions of the impact of each. I also shared the performance feedback I’d received over nearly three years. If that wasn’t enough, every Amazonian has access to all the code you’ve ever written, searchable by alias. In other words: every signal a manager could possibly need, short of a team-fit vibe check.

The third interview was where it went south. Like the two before, it started with canned questions pulled straight from Amazon’s interview bank, a ping-pong of request and response. At least this one didn’t demand I recite everything in STAR format. Still, they read their script, I recited mine. And then came the technical portion, where I really fell apart.

I expected the first two interviews to have whiteboarding challenges, which I had — hopefully outwardly — tolerated with grace. I’d been told the third interview’s technical portion would be design-focused. What I didn’t expect was to be asked to load up the whiteboarding software again - to design Battleship - the game where you guess coordinates to sink ships.

To be clear, it’s not an unreasonable interview question. But in this context, when I’d already shown them production systems I’d designed and supported at scale, it felt absurd. Instead of discussing the tradeoffs behind complex, living systems, I was sketching out the rules of imaginary naval warfare.

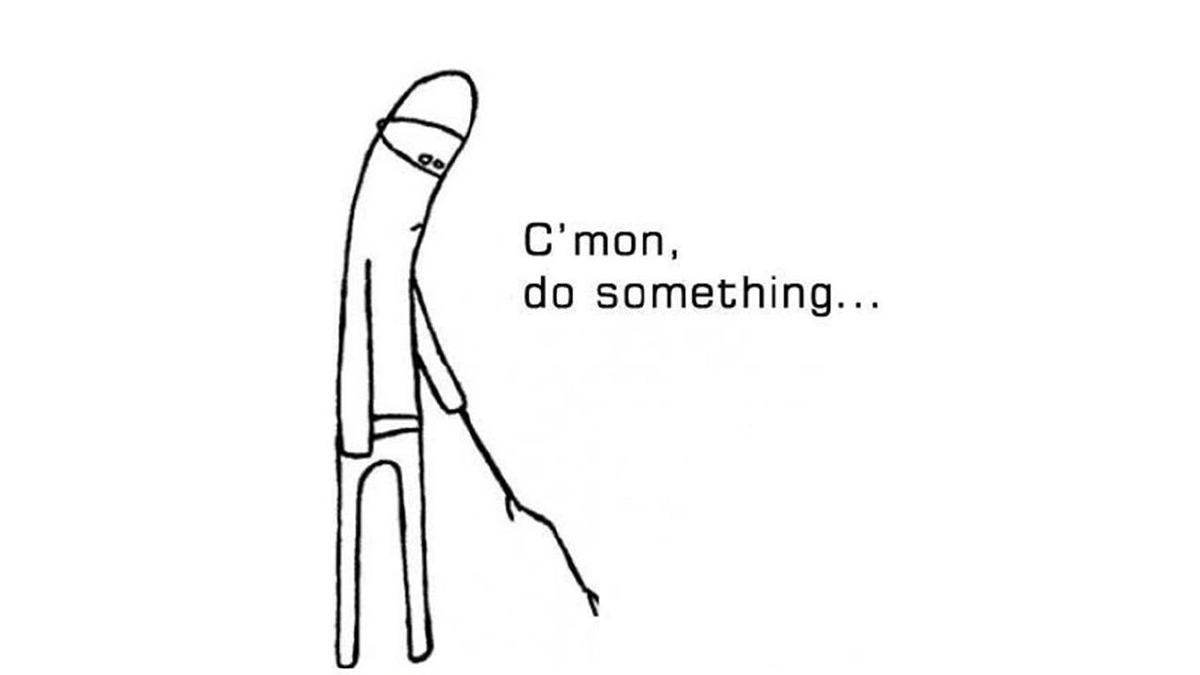

My mind blanked. Not because it was technically difficult, but because the process felt so robotic and impersonal. We were embodying the meme of the person poking a rock with a stick, and I was the rock. I considered ending the loop right there. Instead, I trudged on. I wanted the transfer. I don’t know if he could sense my growing disinterest as he probed for more. What condition would that satisfy? What else is part of Battleship? What does it mean to win? I’m not sure - but nothing about that interview felt like winning.

The fourth interview was supposed to be with the hiring manager. After my third interview concluded, I messaged her weekly for three weeks, before finally receiving a Slack: “sorry, the position has been closed.” She couldn’t spare 5 minutes to close the loop she started. At least she responded unlike ten of the other dozen internal roles I reached out to.

Jumping Through Hoops

Externally, things weren’t much better. I had a call with a recruiter the same day I’d done my groundbreaking work on Battleship. He was personable, articulate, gave me a clear sense of the role. I was interested…until he outlined their process: a two-hour take-home test, a 45-minute manager screen, a two plus hour virtual onsite, a pre-executive briefing, then final interviews with the CEO and CTO. I hesitated.

“Yea, sorry. On principle, I’m not spending two hours on a take-home test before even talking to someone on the team.”

“Understood - we used to actually have it the other way around, but the hiring manager is busy - so we flipped the order. We can reverse it if you’d like.”

I paused. I realized there was no part of me that wanted to do any of it, even with that concession. I wasn’t sure I even wanted to stay in a field where interviews felt like standardized tests without standardized grading, years after I thought I’d already passed. In the realest I’d been in my months of applying, I told him I wasn’t interested, then expressed my general frustration with these interview processes. Not a winning strategy for landing a job, but it spilled out. I’d had enough.

When I joined Amazon, the common wisdom was that the FAANG stamp of approval opened doors. It did shape me into an engineer, and the skills have been invaluable. But the effect on my job prospects? Well, I get less callbacks than when the sum of my experience was a six month stint at a health insurance company.

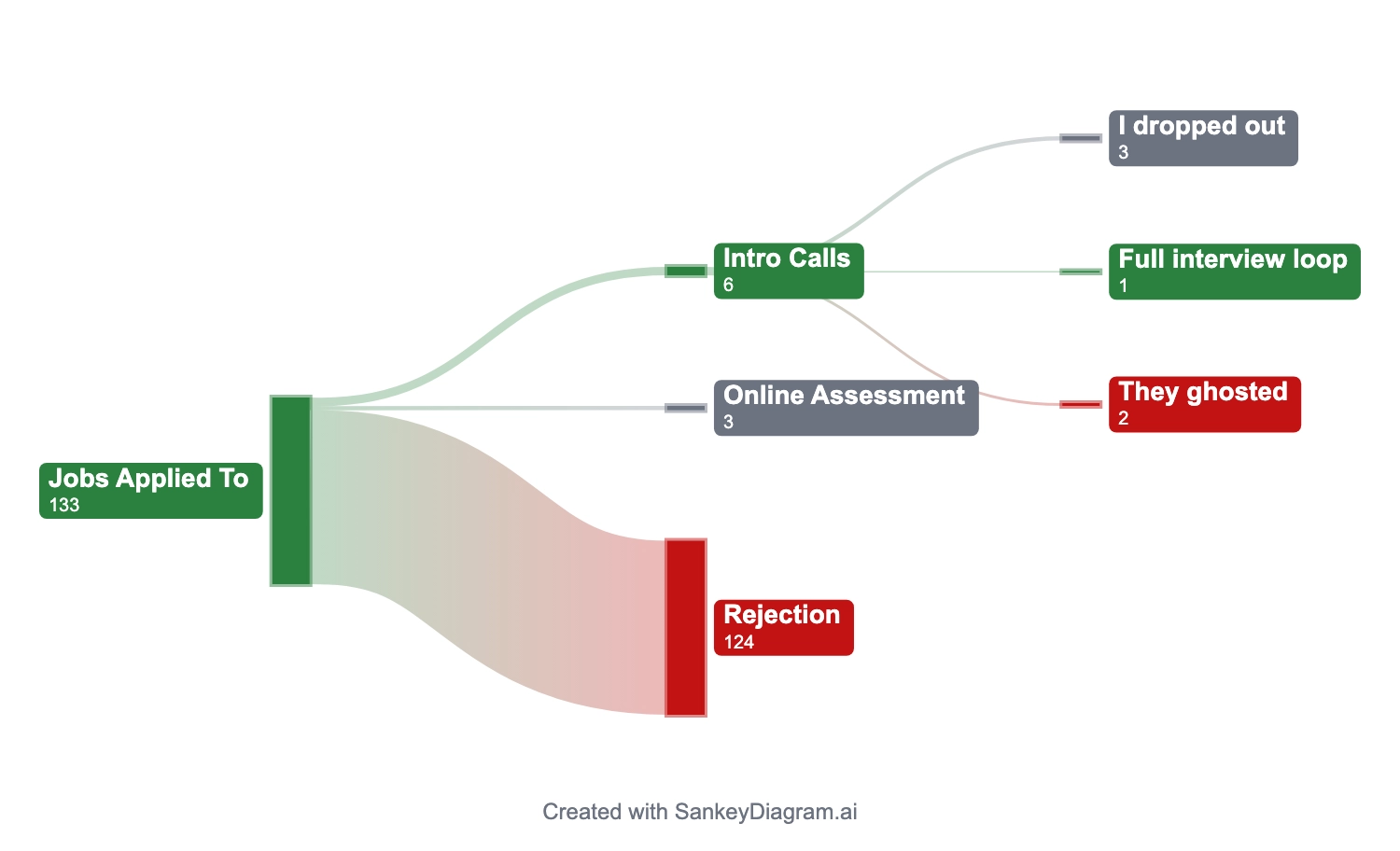

I have a 6.8% callback rate on 133 applications, targeting remote and NYC metro area roles. I’ve had my resume checked by a respected tech career coach and have received an intro call from Netflix, suggesting my resume is not an issue.

Included in that callback rate are mostly intro recruiter calls. Those usually go well. I recite my experience and they say I seem like a potential fit. Occasionally I’m rejected for lacking experience in a specific tech stack - which I’m told is an artifact of an ultra-competitive market, something that used to be extremely rare.

Twice, in place of the standard intro call, I received (and rejected) invitations to online coding challenges. I won’t spend hours coding random garbage without even knowing if a human looked at my resume. One of those required photo ID verification, a recording of my webcam, microphone, and screen while doing the challenge. A third time, I was given a thinly veiled IQ test, which I only agreed to because the company was “prestigious” and the time commitment, an hour. I passed, but the recruiter proceeded to have trouble scheduling the call - she cancelled twice the day-of.

Further along in the process, I’ve been a runner-up called months later, or crushed an interview loop only to be told they filled the position internally. Mostly, it’s silence. And that’s fine for now. I don’t need a new job today. But given increasingly strict RTO (return to office) policies and a company with a recent appetite for RIFs, I’m not exactly comfortable. And I can only imagine what this market feels like for those without a brand-name on their resume, with less experience, or god forbid - new grads.

Disposable Talent

There are a dozen forces that have led to this job market - twice as many CS grads as a decade ago, outsourcing, memeing “learn to code” until too many people actually followed those instructions, the vogueness of cost-cutting, an uncertain economy, and the looming spectre of AI. Though I’m not interested in dissecting the ‘why’. Only the effect.

Interviews are hard to come by - and when you land one, they’re increasingly exacting. The bar feels impossibly high. A non-optimal coding solution. Lack of experience in a single technology. A failed vibe check. Or maybe you crush it with flying colors, but there is someone who is just a little better, with a tad more experience. It feels like tech workers have become disposable - not even worth the courtesy of a reply.

And it’s such a contrast to when I started. When I first joined Amazon, I was excited. Tech felt like a land of opportunity, a meritocracy where talent was rewarded, where the cost of grinding through a tough process and racking up hard-earned experience came with the promise of growth and opportunity. Entering the field, it was impossible not to feel that people with these skills were wanted, companies recognized their value, and the future was wide-open.

Now it feels hollowed out, over-saturated, and cynical — an industry that seems to want you to prove, again and again, in a hundred arbitrary ways that you deserve to even be considered, only to remind you, through endless RIFs and layoffs during record profits, that you’re disposable anyway. What once felt like the ideal career has become something else entirely — a rigged game of Battleship, where you fire blind shots into the void, never sure if a hit is possible, the rules change mid-game, and most of the time no one even tells you whether you missed.